New Online Courses Coming Soon

One reason I wrote this article on cash flow is that a number of you asked for help navigating financial statements and 10-Ks/Qs. The good news is that we are soon launching a series of online courses that walk you through a 10-K, using Apple, Netflix, Microsoft and other popular stocks as examples.

As usual, we shall focus on what to look for in financial data, rather than trying to give an opinion on whether the stock is cheap. (Although regular readers will already know that I have been wondering how Apple has managed to hang on to its premium rating - let’s see what happens when their final results come out soon.)

As a subscriber, you’ll be among the first to know when these courses go live. In the meantime please, send me an email at info@behindthebalancesheet.com if you:

Have stocks you would like us to cover

Have specific problems in understanding the financial statements – we shall try to include help in the course.

Would like to tell us how a course like this should be priced – we would love to get your feedback.

Cash Flow Statement

I have noticed that many people don’t understand the structure of the cash flow statement, nor what goes in and what is omitted. After reading today’s article, you won’t be one of them. Let’s start with the basics.

The Cash Flow Statement has three sections:

1) Cash from Operations

2) Cash from Investing

3) Cash from Financing

Cash from Operations

The first point to note is that there is not a strict standard structure to the Cash from operations section. Under US GAAP, the starting point is always net income and the first section take you to operating cash flow after tax. Under IFRS, however, companies are free to start at EBIT, pre-tax profit or net income.

Because there is this flexibility in the starting point, the reconciliation between profit and cash flow varies depending on where you start:

- Start at EBIT, no need to add back tax and interest

- Start at pretax, no need to add back tax

- Start at net income, you need to add back tax and interest

Source: Hardman & Co

The table shows that there is no consistency, either by auditor or by sector – it’s at the discretion of the Finance Director and is usually a function of history. Let’s assume you start at net income, as that is the most common starting point globally. You first need to add back all the non-cash items to get to a cash flow number.

Non-Cash Items

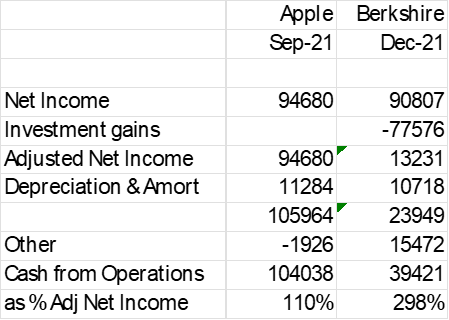

Depreciation – this is a non-cash item and therefore needs to be added back. It’s important to note the difference between a capital light company like Apple and a capital heavy company like Berkshire. The table shows that depreciation is much more significant to the latter and this has important valuation implications, especially if the assets are long-lived.

Source: Behind the Balance Sheet from Sentieo data

Investors value capital light businesses highly, but the more capital intensive business tends to generate a higher operating cash flow for each dollar of earnings. If the assets do not need to be replaced for a long time, the business with the higher depreciation burden may be more attractive than is generally realised. I shall return to this topic in a future article.

Amortisation – like depreciation but this applies to intangible assets.

Gain or loss on sale of assets – if you have sold say a property and reported a profit on the sale, you must subtract this number as the overall amount you sold the property for will be a receipt under Cash from Investing. (If you don’t exclude the profit or loss, you will be double counting). Companies often seek to hide such property sale gains and bucket them with other items, but the keen Analyst can triangulate between the cash flow and the balance sheet to derive the gain – something I explain in my How to Read a Balance Sheet course.

Stock-based comp – this is an addback to net income to derive cash from operations because it is a non-cash item. It is also usually treated as an add back to derive a non-GAAP earnings number. But it is a real expense and often a significant cost to the shareholder. I have written about this in the past and it’s important not to overlook this in your analysis.

Provisions – the difference between the cash spend on provisions and the P&L charge needs to be adjusted here, although it’s often netted off with other items. But if there is a big restructuring provision for example, you will see that the P&L charge is added back here in year one, while the cash spend is often delayed until the following year.

Next let’s look at the adjustments that take you from a company’s Net Income to EBIT.

Net Income to EBIT Bridge

Interest – the cash spend on interest comes under Cash flows from financing activities, so it has to be added back. In theory interest should be all cash, and the numbers should match, but they often do not, for example the unwinding of discounts: where a company has a very long-term liability, that liability is discounted in the balance sheet. Each year, as you get closer to the crystallisation of the liability, the discount unwinds and notional interest is charged to the P&L. It’s not a real number and therefore has to be excluded to derive cash flows.

(This is not a bad way of thinking about the bridge between the P&L and cash flow. The P&L often includes a number of notional items. Cash, however, is real.)

Tax – the P&L tax charge is a non-cash number and therefore needs to be added back. This is a common mistake, even for professional analysts. Two points to note here: 1) the 2021 tax charge against the 2021 pre-tax profit is paid in 2022; 2) tax paid is often less than the tax charge as companies benefit from capital allowances on investment. The accounting rules dictate that the charge in the P&L is smoothed so deferred tax is applied – for deferred, read non-cash. US GAAP Cash flows often refer to the tax add back as deferred tax. I am deliberately engaging in an enormous simplification – tax, especially deferred tax, is an astonishingly complicated subject.

Balance Sheet Moves

The most important changes here generally relate to working capital. The cash flow is adjusted for increases or decreases in working capital and similar assets and liabilities. When a customer pays you, you receive cash and working capital is reduced –this is not shown in the P&L but is shown here in t cash flow.

A company can see a substantial change in cash flow if a customer pays in the last week of the year rather than waiting until the first week of the new year. Working capital moves can be lumpy and if a company has an unusual year-end, then there is more scope to manipulate working capital.

It’s simply good practice to persuade your customers to pay you promptly, but many major corporations take an unreasonably long time to pay suppliers. If you have a December 31 year-end (the most common timing), almost everyone wants to be paid before rather than after year-end. But if you are a retailer (whose year-ends are almost never December 31), there is more scope to finesse the reporting of working capital at the end of the year. So watch for companies with odd year-ends – here is an example:

“The Company’s fiscal year is the 52- or 53-week period that ends on the last Saturday of September.”

Recognise this? Perhaps it would be easier if I repeat the first paragraph of the 10-K:

Yes, it’s the largest company in the world, Apple, and its balance sheet is likely to be favourably presented.

To be clear, while this gives an advantage in that working capital is likely to be lower than otherwise at year-end, it’s the same each year so the cash flow benefit is restricted to the growth in working capital being lower each year than otherwise. I should also emphasise that Apple (and most retail stocks) are not doing anything WRONG, but it’s worth being aware that the average cash may look lower than the year-end position. Other balance sheet moves may be individually reported or may be netted.

Cash from operations then must be adjusted for tax paid to get to cash from operations after tax.

There are a couple of issues on the definition of operating cash flow which I disagree with and are perhaps worth mentioning. For example, I don’t like the effects of IFRS 16, the recent standard on leasing. Its US equivalent messes up the balance sheet but cleverly leaves the P&L (and by implication the cash flow) unscathed – this is intellectually inconsistent and rather surprising, but it’s much better than IFRS.

Under IFRS, the cost of leases is effectively treated as a financing item. This is understandable as the decision to lease a truck or a shop is a financing decision, but it means that operating cash flow trends are inconsistent, especially for companies like retailers.

Impact of IFRS 16 on Tesco Operating Cash Flow

Source: Behind the Balance Sheet from Sentieo Data

The chart shows how IFRS16 boosted Tesco’s Cash from operations – the standard made retailers look more cash generative than before.

Paying subscribers can read on for some commentary on receivable and supplier financing arrangements which are not currently disclosed in the cash flow – regular readers will recall the work which I did on Greensill and the original blog produced with Marc Rubinstein.

Please let me know if this type of article is helpful and we shall continue with the investing and financing sections of the cash flow statement in the coming weeks. I hope this type of educational article can help students and young people interested in investing, so I didn’t want to put it behind a paywall.

In saying that, more of my future content will be going behind the paywall in coming months as I intend to make most of 2023’s content for paid readers. Free subscribers will still receive some articles but I would like to encourage more of you to pay – it takes time to produce these articles and my wife would rather I did the ironing or something. If you enjoy these articles and want to save me from the ironing, please consider joining.