The Substack Gold Rush: Who’s Winning and Why?

Breaking Down the Data on the Top Money-Making Newsletters

I recently realised that I have been writing this Substack for nearly 3 years – I started in March, 2022. I thought this was a good excuse to take a broader look at finance Substacks and to review my journey and future direction.

Finance Substack is a recent phenomenon and has shown impressive growth. From nowhere 5 years ago, I estimate that the top 100 investing Substacks generate revenue of c.$30m pa. That’s small relative to the investment research industry, but can be a sizeable side hustle for some writers.

The original motivation for this post was learning that Rupak Ghose had a Substack with just 800 subscribers. Here is someone who regularly writes for FT Alphaville and has some highly original views.

Substack has become increasingly competitive, unsurprisingly, as there are no barriers to entry and I wonder if marketing skill counts for as much as content quality. One top 20 finance writer on Substack is the inverse of Rupak – he is inexperienced and may have limited investing skill but has excellent marketing nous.

Why is it that someone like Rupak can struggle to get followers, yet others who are inexperienced and likely have lower value add, can attract so much larger an audience? I think there are three main reasons: longevity, content and marketing.

I shall dive into those, look at pricing and then explain my experience with this Substack. It’s a departure from my usual modus operandi, but little has been written about this and I think it’s relevant for investors.

Longevity – One Key to Income

Marc Rubinstein is one of the top 20 finance newsletters on Substack and quite rightly – his Net Interest column is fantastic and one of the few that I try never to miss. He, like me, is a former practitioner at a multi-billion hedge fund; but unlike me, he has real sector expertise. He does all the hard work on a company’s history and business and leaves the reader to cover the last mile of evaluating the current share price.

It’s brilliant, has 90k free subs and must make a good living at nr 16 in finance (I did the analysis a few weeks before this was published) with >1000 paid subs at $25/month or $250/year. He is therefore likely to be generating $250-500k in income.

Similarly, Alex Morris, who produces The Science of Hitting Substack, another excellent writer, was early on Substack. He is nr 31 in Finance Substack and has hundreds of paid subs at $99/mth and apparently, per Matt Levine, earns $260k p.a, twice what he earned in his former role as an analyst at an RIA in Savannah, Georgia. He likely makes a little more now - see below.

Barry Knapp was another early participant and now has 7000 free subs but hundreds of paying subs at $999 pa. He is nr 49 and I am guessing makes $175-200k pa. He has 40 years of experience as a macro commentator, formerly at Lehman, Blackrock and Guggenheim Partners.

John Huber, a guest on my podcast last year, also writes brilliantly. John has 22,000 free subscribers and hundreds of paid subscribers at $60/month. John came in at #39, which probably pitches him at c.$250k pa, per my estimates. He runs Saber Capital but also writes. He has posts on Substack going back 10 years (including his earlier blogs). Nevertheless, he is a more recent addition, bringing his blog over to Substack in early 2023 and then monetising it in late 2023, which suggests that you don’t need to be long established on Substack.

Dirtcheap stocks, a Substack started almost accidentally and only going for a year, recently revealed that his income hit $269k in February, 2025. When I did the analysis, he was at nr 38, 7 places behind Alex Morris. He writes about micro-caps that are trading at below working capital or similar. He started on Twitter and one of the first stocks he posted was trading at a 3x P/E and for less than the cash on its balance sheet. A professional manager messaged him to say thanks, he bought 4% of the company!

Dirt claims that he didn’t have a clue what he was doing and was in any case writing up his own notes so it’s hardly any work to hit publish. With under 10k total subs, he has a 4.5% conversion to paid – a 5% rate was Substack’s original target but this is insanely high, and most people I know or observe have a conversion rate of 1-2%.

Note that these are gross revenue estimates - before fees from Substack and Stripe and fx charges.

Content: Competing with the Sell Side

Content is king but I suspect that marketing is just as important. Certainly, brilliant content without any marketing will bring significant subscribers - Marc Rubinstein is a case in point as his Substack spread largely by word of mouth. When Silicon Valley Bank collapsed, his write-up went viral and I guesstimate he added c.10k free subs in a single week.

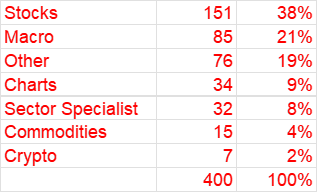

To get into the top 20, where the really big money is made, you need to have great content or fantastic marketing. Doomberg, top of the finance charts, is the best example of being excellent at both. Content varies widely and the table shows there is a wide range of genres within finance Substack:

Finance Substack Genres

Source: Behind the Balance Sheet Estimates from Substack Data

I chose those categories with the help of an AI tool and they seem to make sense, although I have done limited checking of the AI’s categorisation. Just under 40% are on stocks, probably the easiest thing to write about; although picking good stocks and writing well is another matter.

Just over a fifth are macro commentaries, perhaps a reflection of a proliferation of economists? Macro is easy to write about, as there is always something happening in the world, but it’s more difficult to add real value. Who buys most of this is a question for me, but 11 of the top 20 Finance Substacks fall into this macro category.

Other covers a range of categories including some in foreign languages which seem to do well – less competition than publications in the English language. I should probably use AI to translate Behind the Balance Sheet.

Sector specialists should do well, and they are not perfectly categorised here, with some coming under stocks, but they cover shipping, fintech, REITs, levered credit, high yield etc.

The stocks category covers a huge range with 9 of the top 20 and 38 of the top 100. This area overlaps with sellside research, as does macro; my take is that many smaller funds and family offices are using Substacks as an alternative to traditional research sources. Multiple billion dollar hedge and long only fund managers subscribe to my paid Substack, and I also offer an institutional subscription, as does Marc Rubinstein.

For most larger funds, I imagine that a major problem is simply the sheer choice; there is an information deluge, and it’s hard and takes too long to decide which Substacks to read. But the smart money has recognised that sellside research from the big players has become dumbed down and there is a better chance of finding original ideas in Substacks.

Mifid II has been a disaster for sell-side research. Bloomberg estimated that the big banks have cut analyst numbers by 30% in the last decade – I think the answer may be higher as while headcount may be -30%, experience levels are likely -50%. That’s what the spend has done.

Equity Research Headcount at Top 15 Banks

Source: Vali Analytics via Bloomberg

Of course, this trend would have occurred at least in part without Mifid II which was likely just an accelerant. More passive money and less active money means less demand for sellside research. The sellside effectively acts as outsourced expertise for the buyside which cannot afford its depth of sector specialisation.

With fewer active managers managing less money, and with Mifid II forcing many managers to pay for research themselves, the revenue pool available for sellside research has shrunk. And the sellside has focused on larger stocks – 97% of the S&P 500 has 10+ ratings, vs under 70% ten years ago.

Meanwhile, over 3 in 4 of the Russell 2000 have less than 10 analysts vs 44% ten years ago according to Bloomberg. It sounds daft that the sellside hasn’t focused on under-covered stocks, but when you think of the pod shops’ commission vs everyone else, it’s understandable that the banks perceive greater opportunity in the largest and most liquid names.

That appears to be leaving a gap in the market for the independent analyst on Substack. And at least some of them are analysts who lost their seat on the street and have used Substack as an alternative. One, Edwin Dorsey, was all set to start at a hedge fund but it closed before he graduated; and he has established a brilliant reputation as an independent analyst on Substack, age just 26.

It’s not all bad news on the sellside. After 6 years of research spend decline, it may have bottomed, as some firms have realised they cut too far, although others are still trimming research budgets. Substantive Research reckons that global research budgets rose by 2.1% last year.

Marketing

This is critical, in my view – get free subs in at the top of the funnel and if they like what you write, maybe they will end up paying. For me, the Substack recommendation engine has been pretty helpful – I have added 8k subs from recommendations - and there are now 80 Substacks recommending me, which I find mind-boggling.

Some of these are friends, like Marc Rubinstein (Net Interest), Pieter Slegers (Compounding Quality), Jonathan Boyar (Boyar Research), Herb Greenberg (On the Street) and Joachim Klement (Klement on Investing – an excellent free daily, I honestly don’t know how he does it).

Others are people I have met via Substack or Twitter, like the excellent Callum Thomas of Top Down Charts and Frederik Gieschen (Age of Alchemy). Sometimes the flow is in my favour, sometimes the other way round, and often it’s quite even, as with Frederik.

At Behind the Balance Sheet, we don’t do much outside Substack in the way of marketing this newsletter. We have barely used paid ads and we do very little on social media, mainly through our LinkedIN company page. I ought to publicise the Substack more - there is a sign up button on the home page and our usually weekly post on LinkedIN. Otherwise, we rely on Substack’s recommendation engine, on readers sharing articles and on external links to the post – the Financial Times sometimes adds my column to their reading list and that is helpful in generating traffic, as are my occasional appearances on others’ podcasts.

I have an ad for the Substack on my podcast and that must be helpful. Other writers have also found podcast appearances useful in driving traffic and many use social media to publicise their Substacks. I now have more Substack subscribers than my total followers across social media, but I should certainly have devoted more efforts to advertising the newsletter. I also have printed cards which I give away at conferences.

There is no question that the most effective way to grow income is to capture more free subscribers and then coax them to convert – my strategy is to give a generous preview on most posts but to leave a critical element behind the paywall. And I generally don’t discuss individual stocks in the free newsletter, although I do try to deliver real value there.

Pricing

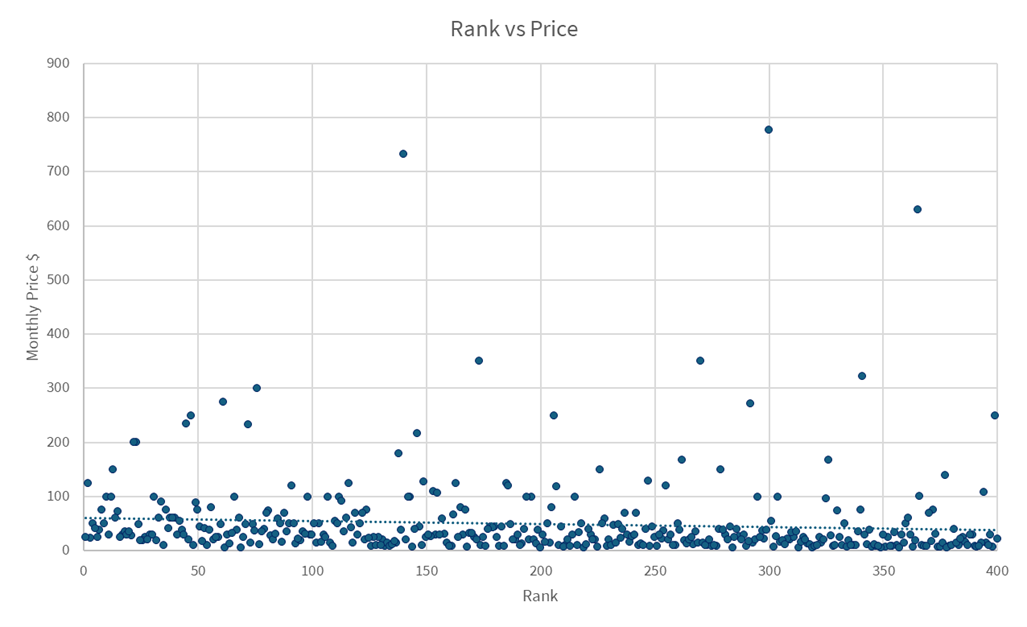

There is no consistency between pricing and ranking – here are the top 400 finance Substacks:

Top 400 Finance Substacks – Price vs Rank

Source: Behind the Balance Sheet estimates from Substack Data

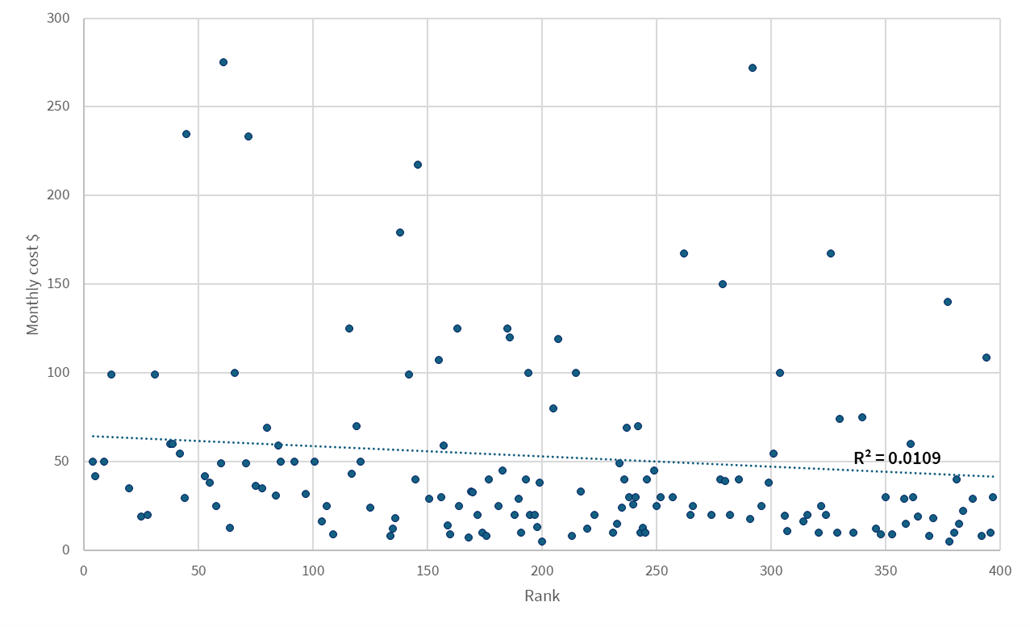

And if we look at the majority which are under $100/month, the pattern looks like this:

Top 400 Finance Substacks <$90/mth – Price vs Rank

Source: Behind the Balance Sheet estimates from Substack Data

Here are the higher priced letters (>$90/mth):

Top 400 Finance Substacks >$90/mth – Price vs Rank

Source: Behind the Balance Sheet estimates from Substack Data

There is no difference between categories:

Macro Substacks Price vs Rank

Source: Behind the Balance Sheet estimates from Substack Data

A pretty random pattern and similarly for the larger category, stocks:

Stock Substacks Price vs Rank

Source: Behind the Balance Sheet estimates from Substack Data

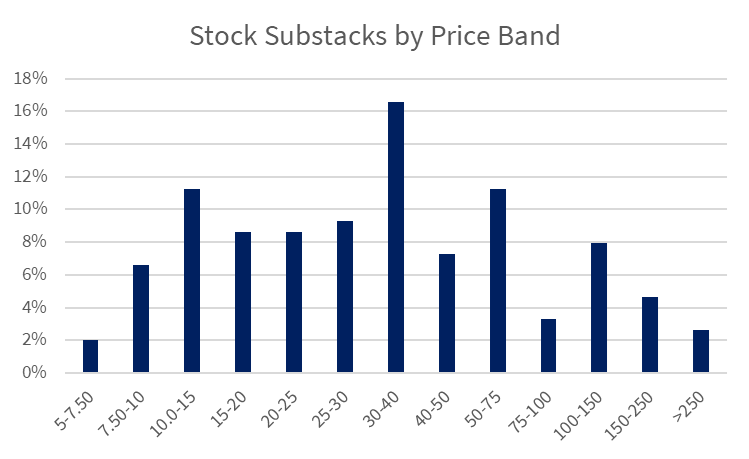

The most popular price band is $30-40/mth:

Finance Substacks by Price Band ($/mth)

Source: Behind the Balance Sheet estimates from Substack Data

Looking at the individual categories paints a slightly different picture, which is interesting:

Macro Substacks by Price Band ($/mth)

Source: Behind the Balance Sheet estimates from Substack Data

Macro tends to be slightly cheaper than stock recommendations, which have an average price 15-20% higher:

Stock Substacks by Price Band ($/mth)

Source: Behind the Balance Sheet estimates from Substack Data

And if you are a sector specialist, you can charge a lot:

Sector Specialist Substacks by Price Band ($/mth)

Source: Behind the Balance Sheet estimates from Substack Data

And for completeness, the other large category is Other which also has the highest average price:

Other Finance Substacks by Price Band ($/mth)

Source: Behind the Balance Sheet estimates from Substack Data

Beyond Finance

The 400 above are all in Finance, but there are some investing related Substacks which are categorised differently, probably by accident. Number 5 in Business is my friend Edwin Dorsey, the brilliant 26 year-old who writes the Bear Cave and has a massive following. At #2 in Business is Noah Smith and at #9 is Danielle DiMartino Booth.

And I have been unable to locate some Substacks. I would classify them as investing but they don’t seem to be on my list. I enjoy David Kim’s Scuttleblurb and he has revealed that he earned $310k in 2024, up 9% y-o-y, of which just under $100k was from Substack – that should place him in the top 100 in finance but I could not find Scuttleblurb in finance; and I believe he may have more than one publication.

LibertyRPF, another finance writer, reported that he made $31k in 2023 from 300 subs, 10% of his base. This was significantly below my expectation, as a subscriber. This is just to flag that the above is not intended to be exhaustive and not everyone is getting rich, obviously.

The Behind the Balance Sheet Substack

I used to write a monthly blog of 2-3000 words and found that a struggle. When Linda Lebrun, who looks after the finance genre for Substack, originally approached me to produce a weekly Substack, I laughed - it sounded like hard work. When she offered me a publishing advance, I became more interested and I thought that it would be a good challenge and might help improve my writing. I also thought that it would be a useful strategy to grow my email list in order to sell more online investor training courses.

It has been a successful venture and good fun. The growth has been decent, but not spectacular. My content generally appeals more to experienced investors, a much smaller universe than beginners. But I have a decent subscriber base (which includes c.1000 asset management firms) and income, and I enjoy the challenge of a weekly column. It offers me an excuse to research areas of interest and an unexpected bonus has been the impetus to attend more events and conferences and be forced to listen carefully – having to write up the story afterwards means I have to pay attention.

I started out at $15/month which was a stupid decision and left a lot of money on the table – I gradually increased it to $20/month which I felt was fair, relative to other finance Substacks - for example, Net Interest was $25/month. I offered an annual subscription at $350, aimed at professional investors who wanted to reward me for the work, leaving the monthly rate readily accessible for the private investor whom I wanted to encourage. The monthly/annual price gap caused some confusion, but generated additional revenue.

One partner of a $20bn hedge fund signed up each year to get the Sohn write-up for $20, then immediately cancelled. I intended to raise the price to $100 temporarily for that issue in 2024, but rethought that and settled at $35/month, in line with the annual $350 level, and I have left it at that. This research has confirmed that that is probably the right amount.

Obviously, if a reader gets one good idea, that is enough to pay for several years’ subscriptions. Meanwhile, there is a substantial cost involved in the production. Substack takes 10%, Stripe 3%, then there are fx fees on top and now VAT in Europe (see below). I go to conferences and similar events to write about them. Once travel and hotels are included, that cost is substantial, some 20% of net revenue. The Substack is my least profitable business line based on revenue per hour, but it’s good fun and will likely generate another book or two.

I used to edit the articles and sell them to UK publications like Investors Chronicle and Moneyweek, but have been doing less of that in the last 18 months. I should try to sell some of the content more widely, for example to US or Australian publications, but it’s a question of time.

Free subscribers will see (I hope) a growing number of ads, which premium subscribers are spared. They can read on to find out where I rank in the top 100, to get my subscriber numbers and income and to download a sheet of the top 400 Finance Substacks categorised with monthly charges in dollars.

Thank you for your support!

Note for Substack writers: Now, if you sell digital products into Europe, you have to pay European VAT, even if you are based in the UK or US. That’s a c.20% hit to those revenues - each country has a different VAT rate so you have to work out how much VAT you owe quarterly. I can explain more to any fellow writers on Substack who want to get in touch, and am lobbying for Substack to add the VAT to the subscriptions automatically.