In this post, I’ll outline my key takeaways from Lee Freeman-Shor’s book, The Art of Execution.

I read the book on the recommendation of my friend, Stacey Fikes. I think it’s well worth a read and my publisher, Harriman House, is offering a discount to my subscribers. If you’d like to pick up a copy, you’ll find your discount code at the end of this post.

Freeman-Shor ran a fund of funds, with the twist that his investees were asked to pick their 10 best ideas. In this book, he analyses how many of the stocks were winners or losers. He then looks at how the managers handled those winners and losers, and assesses their differing strategies.

Investing in just 10 top ideas from elite fund managers should have shot the lights out, you would imagine. Yet their performance was far from stellar. Of 1866 stocks, 946 lost money – so his win rate, at 49%, was worse than tossing a coin.

Despite this, Freeman-Shor still made money – and there are some useful lessons to learn.

The 49% win rate was worse than a coin toss

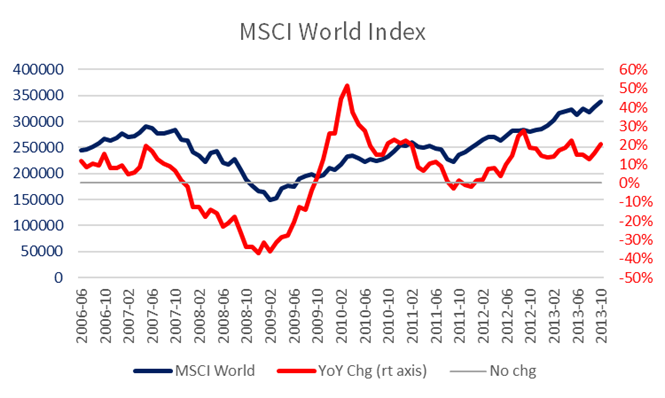

The author examined 30,874 trades in 1866 investments by 45 of the world’s top investors between June 2006 and October 2013. The chart below shows the MSCI World Index over that period, as limited data is given on the universe of stocks selected.

Global Stocks in the Period

Source: Behind the Balance Sheet from curvo data

The extreme volatility around the GFC surely must have affected the results, but there is no reference to this in the book. Nevertheless, there are some important lessons to learn here. Most impressively, the author groups the behaviours of his investees by allocating them to 5 tribes.

Rabbits

This was the tribe of losers, unfortunately for the author, as on average he allocated over $50m to each of them. Some of the most prestigious names on the street bought stocks, watched them go down, and did nothing. Perhaps hoping for a recovery to their purchase price.

They failed to cut these positions in a timely manner, even when their thesis changed and often continued to look at the stocks through the lens at the time of purchase. Freeman-Shor wanted them to review the positions dispassionately, and either average down or sell. This is certainly the correct strategy for a loss-making position, and one which should be easier for the professional investor to adopt than the private investor, who usually has less practice.

The author attributes this attitude to fear of the unknown – if they sold, the shares might rally. So in their mind, it was better to stick with a loss-making position than risk this. I don’t know if it’s fear of the unknown, loss aversion, or some other bias. But this is probably the most common way private investors lose money.

Assassins

By contrast, these investors were quick to cut losers. They focused on capital preservation and when a stock went down, they sold. These investors used stop losses to cut positions at down 20-33%, irrespective of the narrative. This is more of a trader mindset than a long term investing mindset and personally I would find it hard to implement such a strategy. If I had made that mental leap, though, it would probably have made me money.

The author mentions that he finds it hard to let go after realising a loss and continually checks the share price performance after he has sold. This is not one of my habits, fortunately. I think it’s useful to check back, say 3 months later, and see if you made the right decision. But castigating yourself is a waste of time and emotional energy.

Hunters

This tribe averages down on losing positions. Interestingly, they planned beforehand to buy more shares if the price fell. These investors practised dollar cost averaging and didn’t put a full position on straightaway. Many were value investors and were buying out of favour stocks, so they understood that the price might well go against them.

The author suggests that many of these investors were adept at using charts to finesse their entry points and picking the bottom. But if they didn’t get this right, they were not afraid to increase their position, doubling or trebling their commitment. Conversely, they were not afraid to sell if they realised they had made a mistake – this combination of selling the mistakes and doubling up on the winners is a sign of a superior investor.

I was curious as to how many of the group fell into the different categories. I suspect hunters would have been the rarest tribe, but unfortunately the book does not go into those details.

The author points out that his investors generally remained optimistic in the face of a losing position, insisting that the fundamentals had not changed. Yet the majority did not buy materially more shares. This was a serious mistake and is probably the most important takeaway from the book.

Raiders

This tribe likes to bank a quick profit. There seems to be nothing wrong in such a strategy, but of course it means that you will likely miss out on big winners. In my experience, outperformance each year usually arises from one or two big winners.

The author points out that one of his investees had a phenomenal hit rate – 70% of his ideas made money, which is unusually high. Yet he didn’t make any money overall, because he would immediately bank a small gain of say 10%. A few large losers were then enough to wipe out all of the gains, and these investors apparently had a “rabbit” mindset when it came to losers.

A combination of a “raider” and “assassin” approach would presumably be more likely to make money, but the author didn’t encounter this. This is interesting as I would have assumed the two strategies would be natural bedfellows.

The author surmises that these investors sold quickly, mainly because they got bored or because of the pleasure of banking gains. The boredom rationale is one I have experienced – I have at times got fed up waiting for the market to appreciate the unique qualities of something I have held. I am not sure that is a mistake.

Connoisseurs

This, as the name implies, was the most successful tribe. They ran their winners but were also effective at cutting losers. Interestingly, they were worse than average at stock-picking – they were right only 40% of the time. But when they won, they won big.

These investors tended to focus on quality companies with high predictability. They bought stocks with significant upside potential and they took significant positions – some had 50% of the portfolio in just 2 stocks (remember these were 10 stock portfolios).

Conclusion

The Art of Execution is well written, and identifying investors by tribes is a clever idea.

For me, the main takeaway was that the best investors execute with precision. Because of this, they can still make money, even though most of their ideas are losers. To an analyst who focuses on stock selection, this was an important learning.

Free subscribers can buy the book from Harriman House and get 10% off with the code AOE10.

Paying subscribers get a bigger discount with the code provided in the premium section below. This section also has my thoughts on what to do when a position goes against you, and how I currently approach selling positions.

Footnote for free subscribers, repeated for paying subscribers below

I have pledged the advance for the Russian rights to my book to my friend Whitney Tilson who is buying 25 ambulances for Ukraine. You can read the story of his adventure and mail him at WTilson@tilsonfunds.com for details on how to donate. I promised to donate last Sunday when I read his email and in a week he has raised more than the $2.5m he needed. Being college room-mates with Bill Ackman helps. Worth reading the story though - Whitney is really a wonderful human.