Family businesses are at the heart of the world’s economic system – they employ the majority of the workforce and contribute over half of GDP, and even more in many Latin American and some Asian economies.

Family Businesses Relevance

Source: Tharawat Magazine

But this is not confined to small and medium enterprises. Family-owned businesses (FOBs) are also widespread in stockmarkets. As a group, they have consistently outperformed in most regions, as shown in the table below, sourced from the 2023 Credit Suisse Family 1000 (waiting for the 2024 edition).

Relative performance statistics since 2006 – Family 1000 versus non-family

Source: Credit Suisse, Refinitiv

And over the long run, there has been a significant cumulative outperformance, as per the chart below:

Family Owned Business Outperform

Source: Credit Suisse, Refinitiv

This is not new news and ordinarily, such performance would be quickly arbitraged away. Although there are various funds which seek to capture the benefits of a founder led mentality and a risk averse management, the relative outperformance has persisted, and it’s worth asking why.

Harvard Business Review

Various studies have been conducted, including one published in the Harvard Business Review over 10 years ago now. They looked at 149 family-controlled public companies with revenues >$1bn and created a comparison group of companies from the same countries and sectors; these were similar in size but not family controlled.

They excluded Asia because the high preponderance of family controlled businesses made it hard to form a control group. The companies were therefore from the US, Canada, France, Spain, Portugal, Italy, and Mexico. The HBR analysis concluded that family owned businesses do less well in good times, but more than catch up in bad times.

Performance in Different Economic Phases

Source: Harvard Business Review

They reasoned that family businesses focus on resilience more than performance. The CEOs of family-controlled firms have similar financial incentives to those of non-family firms, but their familial obligation leads to different strategic choices. Executives of family businesses often invest with a 10- or 20-year horizon, focusing on the next generation. They also tend to manage their downside more than their upside. This is in contrast to most CEOs, whose incentives focus on outperformance.

The HBR article identified 7 differences in approach:

1: They’re frugal in good times and bad.

Most of these companies don’t have luxurious offices. One CEO told the researchers, “The easiest money to earn is the money we haven’t spent.” They do a better job of keeping expenses under control.

2: They keep the bar high for capital expenditures.

Another CEO told them, “We have a simple rule - we do not spend more than we earn.” Because they’re more stringent, family businesses tend to invest only in stronger projects.

3: They carry little debt.

The firms they studied were much less leveraged than the comparison group; debt accounted for an average of 37% of their capital over a 9 year period, vs 47% of the non-family firms’ capital. As a result, the family-run companies didn’t need to make big sacrifices to meet financing demands during the recession

4: They acquire fewer (and smaller) companies.

Management of public companies are often incentivised to roll the dice and make transformational acquisitions. Family businesses tend to avoid these deals and go for smaller acquisitions, closer to their existing business.

There were significant exceptions to this rule—when the traditional sector faced structural change or disruption, or when not participating in industry consolidation might endanger long-term survival. But generally, family companies aren’t energetic deal makers. On average, they made acquisitions worth just 2% of revenues each year, vs 3.7% pa for non-family businesses.

5: Many show a surprising level of diversification.

Plenty of family-controlled companies (they cited Michelin and Walmart) remain focused on a single core business, but they found a large number of family businesses—they cited Cargill, Koch Industries, Tata, and LG—were highly diversified. 46% of family businesses were highly diversified, vs 20% of the comparison group. Diversifiication was often seen as a way of building resilience.

6: They are more international.

Family-controlled companies have been more ambitious in overseas expansion with 49% of revenues from outside their home region, versus 45% at non-family businesses.

7: They retain talent better than their competitors do.

Retention at the family-run businesses was better with a turnover of 9% pa of the workforce, vs 11% at nonfamily firms.

McKinsey Study

Their study is somewhat out of date and a more recent study by McKinsey confirms many of these hypotheses. McKinsey identified four critical mindsets:

1. Purpose beyond profit: Purpose is embedded in the culture and is a guiding force for the organisation.

2. Long-term perspective: Leaders look beyond short-term results and invest in the future.

3. Cautious financial stance: Leaders’ conservative approach affords them independence and resilience.

4. Efficient decision making: Processes are centralized and streamlined

and five strategic actions:

5. Diversified portfolio: A significant share of revenues comes from beyond the core business.

6. Dynamic resource allocation: Leaders actively reallocate resources to businesses and regions that create growth.

7. Capital efficiency and operational excellence: Outperformers are both efficient investors and operators.

8. Relentless focus on talent: Outperformers are committed to attracting, developing, and retaining the best talent.

9. Strong governance processes: Outperformers have robust mechanisms for ensuring continued high performance across generations.

The two studies paint similar pictures. McKinsey then compared the performance of the two groups and concluded that family-owned businesses have survived and thrived over decades because they are adaptable and resilient. They enjoy better returns overall:

Returns above Cost of Capital: Family-owned businesses do better

Source: McKinsey

The firm makes a distinction between midsize family-owned businesses which they see as more efficient investors – evidenced by higher capital turnover differential in the table - while they see large family-owned businesses as more efficient operators – as seen in the higher margin differential:

ROIC contributors, by size, family-owned businesses (FOBs) and non-FOB

Source: McKinsey

They also contend that the better family owned businesses have a bigger differential in performance - the best family owned businesses are better than other businesses by a bigger margin than the less well performing.

Performance Differential by Return Quintile

Source: McKinsey

Mckinsey share similar conclusions to the HBR study, although they express it in a different way. Using the HBR bullet points:

1: They’re frugal in good times and bad: Margins are higher

2: They keep the bar high for capital expenditures: Returns are higher

3: They carry little debt: Here is the McKinsey chart on leverage:

Average net debt-to-equity ratio, family-owned businesses (FOBs) and non-FOBs %

Source: McKinsey

4: They acquire fewer (and smaller) companies: Not really covered in the McKinsey research.

5: Many show a surprising level of diversification: The table summarises the McKinsey analysis:

Share of company revenues outside core (% Respondents)

Source: McKinsey

6: They are more international: Not covered

7: They retain talent better than their competitors do: Not covered

Credit Suisse Study

The best and most consistent study of the performance of quoted family businesses is the Credit Suisse Family 1000, which has not (yet) been published this year – I have used the data from last year’s study.

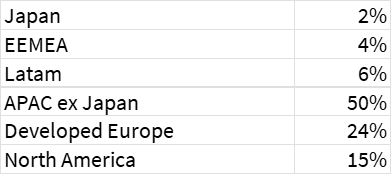

The CS Family 1000 offers the following breakdown of the universe by geography:

Family Owned Businesses by Geography

Source: Credit Suisse

The US market stands at 60% of the global stock market capitalisation, and if US firms represent only 15% of the related global number of companies, it’s clear that companies have largely outgrown their founders there – although even if Microsoft no longer qualifies as a family owned business, Meta and Alphabet do, as does Berkshire.

But the real takeaway here is not that Asia Pac is so significantly represented – partly a function of the age of the emerging capital markets. Rather it’s the importance of developed Europe, influenced by the inclusion of luxury operators, LVMH, Hermes and L’Oreal.

Family Owned Businesses by Sector

Source: Credit Suisse

Consumer discretionary is the standout, again influenced by luxury, while industrial are influenced by the car manufacturers VW, BMW and Geely (not separately listed but presumably included).

The 2023 list of largest and oldest family companies by region is shown In the following table with the companies qualifying as both oldest and largest highlighted.

Big and old quoted family owned businesses

Source: Credit Suisse

It’s my hypothesis that if owning family owned businesses can help your performance and owning long established companies is similar, then owning old and large family-owned businesses is likely a safe strategy (not investment advice).

Podcast

I shall return to the subject of family owned businesses in part 2 next week. Before I go, though, a word about the podcast I published last week. I am selective when inviting guests, ideally preferring highly successful investors who have never done a podcast before (John Armitage, Stuart Roden, Jeremy Hosking etc). Obviously there is a limited supply of such candidates; usually, there is a good reason why they haven’t done a podcast – they don’t want the publicity.

And I have of course invited others, mainly authors. The current guest is an author and has been an angel investor but the reason I invited him is because of his highly unusual private life – it has seen one tragedy follow another:

Two of his three sons lost to suicide

Their mother died unexpectedly

His sister lost to alcoholism

His brother died aged 21 from cancer

Two decades in recovery from alcoholism

Now diagnosed with terminal cancer.

I read about this and wanted to interview him, thinking that I would use it for my YouTube channel where I have interviewed several guests outside the main audio podcast. But in the weeks between the recording and the publication, every day I thought of Peter Cowley and felt grateful for my own and my family’s health and welfare.

I know others who have been touched by the suicide of a young man, extraordinarily the most common cause of death among young men age 25-34 in the UK. And I wanted people to be aware of this.

Don’t worry, I don’t plan to switch genres. Normal service will be resumed in two weeks. We shall publish a celebration of Berkshire to coincide with the AGM, when I interview an extra special guest.

But I wanted to explain my rationale – this has been a highly unusual and quite an emotional experience for me. I sincerely hope hearing this story might help others.

Premium subscribers get a spreadsheet of the world’s 750 largest family businesses, private and quoted.