Does Quality Work?

I wanted to share a couple of studies looking at quality stocks. The first is Amundi Asset Management’s Revisiting Quality Investing, a 100-page paper from last year. The second is a public but unpublished study by Invesco which their chief investment officer (CIO) recently discussed at a conference.

The Amundi paper (or book) set out the best way to define quality as a factor. Stocks were grouped into quintiles according to various quality criteria and their performance following the global financial crisis analysed, from 2007-2020. There was a striking difference between the lowest and highest quality stocks:

Annualised Excess Returns

Source: Amundi AM from MSCI, S&P Compustat, S&P Capital IQ

The authors divided the quality baskets into different factors:

Source: Amundi AM

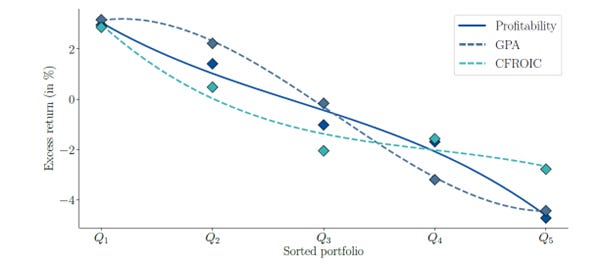

By using two metrics to define each factor, there is less chance of misclassification. (Whether these are the best bases to look at is a subject for another article.) The results in performance terms for each are shown in the chart, again breaking each factor into quintiles.

Annualised Excess Returns by Factor

Source: Amundi AM from MSCI, S&P Compustat, S&P Capital IQ

The profitability metric, which is really a returns-based metric, shows the most significant performance variation between best and worst quintiles, and it’s here where we should focus. The authors suggest that the risk-adjusted return will improve by using all the factors together as shown in the multi-dimensional scores in the table, but while multi-dimensional might be more effective for quants funds, it’s obviously of less use to private investors.

The table highlights a small improvement overall in returns and a lower volatility, but it’s not consistent across geographies and I just don’t think many serious investors care as much about volatility as the academics (and perhaps some wealth managers).

Long/Short Performance Statistics

Source: Amundi AM from MSCI, S&P Compustat, S&P Capital IQ

Globally, profitability is the best factor by far, but combining it with the others does improve results slightly (by 0.5% as highlighted, which is significant) and lower volatility (1% as shown in the line below the highlights). Let’s just focus on the advantage of the multi-dimensional vs returns alone:

Long/Short Performance Statistics

Source: Behind the Balance Sheet from Amundi AM plus MSCI, S&P Compustat, S&P Capital IQ

For simplicity, I show the performance improvement and reduction in volatility by looking at the arithmetical differences and the risk returns using a geometric calculation. It’s interesting that in two regions out of five, it’s better to use the returns or profitability metric alone. I don’t know why this should be, but it strongly suggests that returns are a safer filter. And that’s consistent with what we would have expected.

Interestingly, when the profitability metric is analysed between its two components, it’s gross profitability which is much superior.

Annualised Excess Returns

Source: Amundi AM from MSCI, S&P Compustat, S&P Capital IQ

If the authors had stopped there, it would have been a great study and would have confirmed my prior beliefs. But they introduced a further refinement which was breaking the performance down into time buckets. But before covering that, which I intend to do in my next article, I wanted to drill down further into the returns and look at the persistence of returns.

Persistence of Returns

Invesco have produced some interesting research about persistence of returns and how this affects stock market relative performance. Its UK CIO, Stephanie Butcher, presented a chart at a recent public conference, but Invesco’s compliance department refused me permission to reproduce it. Instead, I have shown the results as published in the table below.

My table is less attractive but simpler than their graphic. The way to think about this is that they divide the MSCI EMU Index (currently 233 stocks in the universe, weighted to France, Germany and the Netherlands), and divide them into 16 buckets. The starting Return on Invested Capital or ROIC is divided into quartiles and they then look at where each stock lies in the ROIC quartile five years later to get the 16 buckets.

So if you start in the top quartile and end in the top quartile, you are in the Q1 starting bucket and Q1 ending bucket, which occurs for 56% of the Q1 stocks as shown in the table. They then show Q1 stocks which end in Q2, Q3 and Q4. The last column shows the relative performance over a five-year period. This was done starting in July 2010 and ending in July 2015, then repeated monthly until September 2021.

Invesco Quality Persistence Study

Source: Behind the Balance Sheet from Invesco data

One important point to note is that 233 stocks won’t fall evenly into 16 buckets of 14-15 stocks. The sample size is in my view too small to be conclusive, but it’s interesting that it corresponds closely to my hypothesis.

The most important point to note is that the most frequent bucket pairs are Q1/Q1 and Q4/Q4. Good companies tend to stay good and bad companies tend to stay bad. And you get well rewarded for buying the first and avoiding the second, 5% relative in each case – this is a sensible strategy to follow.

I was quite surprised that buying a bad company which improved significantly didn’t get rewarded more highly – buying a Q4 company which improved to Q1 only beat a company which started in Q1 and ended in Q1 by 3%. Buying a Q3 company which ended in Q1 was slightly better. This profit improvement strategy is the one I followed when I was at the hedge funds and that delivered hugely better relative performance.

Another way of looking at the data is to segment it by the ending quality bucket, again with Q1 being a good company and Q4 being a bad company.

Invesco Quality Persistence Study

If you end making high returns you will make good money, and if you end making poor returns you will lose money vs the benchmark. Stocks which stay in the middle perform like the average and if they slip, performance is significantly weaker.

As I say, the sample size is small and I don’t place too much emphasis on it, but I would like to look for some wider studies, and I am sure there will be a number. I shall return to the subject of how such quality strategies perform in different time periods as that is really significant at this juncture. But buying quality has worked and good companies tend to stay good companies which sustains the relative performance.

Paying subscribers can read on to learn how this translates when the same principles are applied to a broader universe and to see which sectors exhibit the best and worst persistence.