Background

In the early 2000s, in one of my original attempts at angel investing, I was a partner in a UK clone of American DVD rental company, Netflix. We got off to a good start but needed more capital, which was harder to find back then. I persuaded Stelios Haji-Ioannou, the founder of budget airline easyJet, to inject additional capital, but the deal fell through. The business was eventually sold to LoveFilm before it was in turn bought by Amazon.

I should have just bought Netflix stock. It would have been easier and, had I held it, far more profitable. Today, I am a Netflix customer and a great admirer of Reed Hastings, the co-founder and chairman, but I have had differences with the company – and one of its major backers – over its accounting for content. I originally looked at this two years ago and think it is timely to revisit now that spending on content is increasing again.

Introduction

I believe that Netflix has been aggressive in its accounting for some time. Consider the way it used to account for DVDs: Blockbuster treated them as stock, while Netflix changed its policy to treat them as fixed assets, I believe. This allowed Netflix to report a higher level of earnings – and a much higher operating cash flow, since DVD purchases were treated as an investing item (and hence did not affect the operating cash metric). This was a much less conservative policy in my view, and I shall explain the cash flow impact in a future article (for paying subscribers) on cash flows.

Content Accounting

In this article I consider how Netflix accounts for content. I should just highlight that at least until recently, nobody has bothered too much about Netflix’s earnings. So whether it adopts a more or less conservative policy might have a limited impact on its share price.

Netflix’s policy is to capitalise content costs and write them off over their expected life. That amortisation is accelerated, as most viewing takes place when the content is new, and the life is no more than 10 years, with 90% in the first four years.

For those like me who are pedantic in such matters, here is the policy from the accounts:

“For produced content, the Company capitalizes costs associated with the production, including development costs, direct costs and production overhead. Participations and residuals are expensed in line with the amortization of production costs.

Based on factors including historical and estimated viewing patterns, the Company amortizes the content assets (licensed and produced) in “Cost of revenues” on the Consolidated Statements of Operations over the shorter of each title's contractual window of availability or estimated period of use or ten years, beginning with the month of first availability. The amortization is on an accelerated basis, as the Company typically expects more upfront viewing, and film amortization is more accelerated than TV series amortization. On average, over 90% of a licensed or produced content asset is expected to be amortized within four years after its month of first availability. The Company reviews factors impacting the amortization of the content assets on an ongoing basis. The Company's estimates related to these factors require considerable management judgment.

The Company's business model is subscription based as opposed to a model generating revenues at a specific title level. Content assets (licensed and produced) are predominantly monetized as a group and therefore are reviewed in aggregate at a group level when an event or change in circumstances indicates a change in the expected usefulness of the content or that the fair value may be less than unamortized cost. To date, the Company has not identified any such event or changes in circumstances. If such changes are identified in the future, these aggregated content assets will be stated at the lower of unamortized cost or fair value. In addition, unamortized costs for assets that have been, or are expected to be, abandoned are written off.”

Conservative Amortisation Test

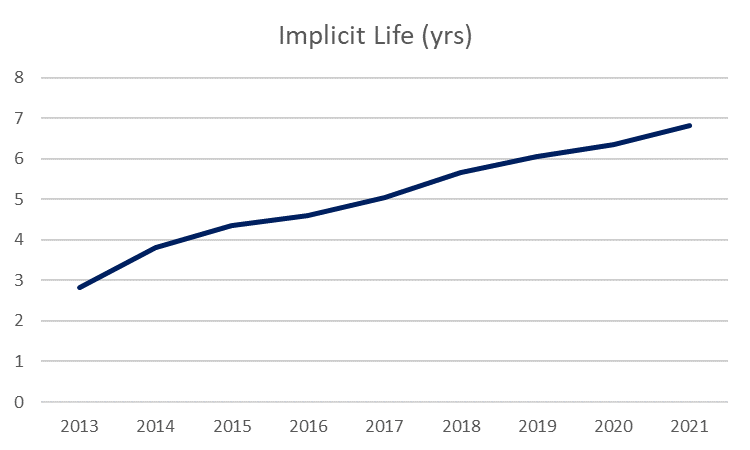

The first test I recommend when looking at capitalised intangible assets is to determine the average life by comparing the amortisation charge with the average asset. My calculation adds back the cumulative amortisation to the net figure shown in the balance sheet and then averages it (the calculation is in the spreadsheet for paying subscribers). Note that formerly, Netflix split out the current content assets but no longer does so for technical reasons – with this more refined approach, the average life was six years in 2019 vs 6.8 years on our new basis.

The trend for Netflix is shown in the chart below, which clearly shows that Netflix continues its trend of becoming less conservative in its content life assumptions.

Netflix Content Average Amortisation Life

Netflix appears open and helpful about its content accounting policy, even producing a video on the subject. In a helpful presentation, Overview of Content Accounting in January 2018 (since updated ) indicated that you should not apply this test, and gave the following justification:

1 The content library is presented net of amortisation, not on a gross basis

2 Content is amortised on an accelerated basis

3 Amortisation in any given period is also affected by the mix of content as different categories of content are amortised on different schedules (based on historical and projected viewing patterns)

In an earlier blog, I explored these arguments

1) As the content is presented net, my calculation of the average life adds back the cumulative amortisation to date. It’s possible that some assets have been fully amortised and should be eliminated from the calculation. Therefore, I may have included in my calculation the amortisation of an asset which has been fully amortised. This would lengthen the life in the chart, but would not be sufficient to create this trend, as Netflix has been increasing its spending on content significantly – the fully amortised assets would almost certainly be a lower proportion of the total.

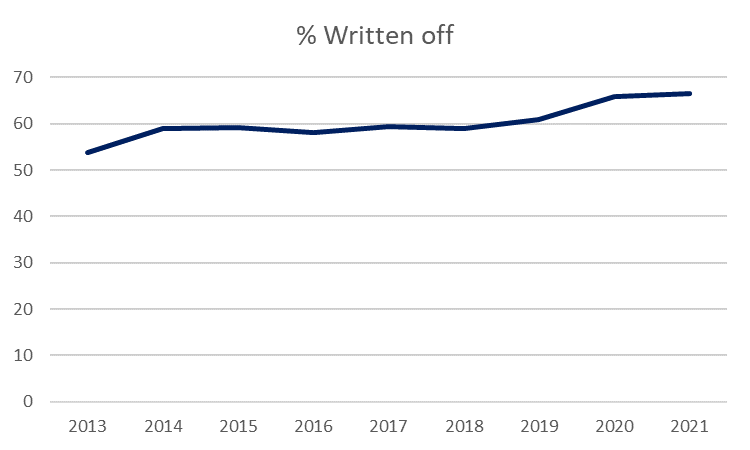

Netflix Average Content Age/Percent Amortised

The chart shows that the percentage on average written off at Netflix has risen from 60% to 66% over this period, an indication of some ageing of the portfolio. Netflix’s spending has been accelerating – in the past three years it spent more than in the previous eight. The fact that the asset is ageing argues that the company is not being super-aggressive. But if 90% was written off in four years, I would expect the profile of the lives to be shorter and the ageing to be older.

2) If content is depreciated on an accelerated basis, there should be an obvious gap vs a straight-line writedown. Here is an extract from Netflix’s accounting policy in the 10-K (2021, p44-5):

“The amortization is on an accelerated basis, as the Company typically expects more upfront viewing, and film amortization is more accelerated than TV series amortization. On average, over 90% of a licensed or produced content asset is expected to be amortized within four years after its month of first availability”.

I tested this by amortising additions to content STRAIGHT LINE over four years to a 10% residual value, then compared with the Netflix amortisation charge. The results are shown in the next chart:

Is the Netflix Amortisation Charge what you would expect?

Clearly, I would expect the actual charge in Netflix’s financial statements to be considerably higher than my estimate, reflecting that content was being written down at an accelerated rate. I cannot understand why Netflix’s amortisation charge is not higher.

3) The question of mix is covered by the policy stating that on average 90% of content should be depreciated within the first four years.

Conclusions

I continue to believe that the content numbers at Netflix are inconsistent with the company’s stated policies. That is rarely a positive for investors. To value the company, it would be better to use the cash spend as a proxy for the expense.

More significant, I explore below (paying subscribers only)

1 Why this is important to the share price

2 Why I think Netflix itself may be concerned