Thank you

Thank you for reading Behind the Balance Sheet — your support allows me to keep writing and I am learning a lot from this weekly production. It was fantastic to be featured in the FT last week, thanks to that journalist - I owe you a beer! Welcome to the 100+ new subscribers who joined that day.

If you enjoy my work, it would be great if you could please invite friends to subscribe. To incentivise you, we have a new rewards program.

How to participate

1. Share Behind the Balance Sheet. When you use the referral link below, or the “Share” button on any post, you'll get credit for any new subscribers. Simply send the link in a text, email, or share it on social media with friends.

2. Earn benefits. When more friends use your referral link to subscribe (free or paid), you’ll receive special benefits.

Get a 1 month comp for 3 referrals

Get a 3 month comp for 5 referrals

Get a 6 month comp for 25 referrals

To learn more, check out Substack’s FAQ. Thank you!

New Book/Competition

My friend Algy Hall has just had his book published by Harriman House. They have kindly offered 3 books as prizes and a discount code to my lovely readers. BTBS30 will give you a 30% discount on the print and eBook version on the Harriman House website, valid until 30th June (including free UK postage.

The competition question is based on conducting the Momentum screen from Algy’s book, Four Ways to Beat the Market, on the top rated companies in the Citywire Elite Companies database. These eight stocks are all in the database of the biggest bets of the world’s best fund managers and also pass the Four Ways to Beat the Market screen for share price and earnings momentum:

Addnode (SE:ANOD.B)

Axis Bank (IN:532215)

Beijing Kingsoft Office Software (CN:688111)

Cholamandalam Investment and Finance (IN:511243)

Dino Polska (PL:DNP)

Ecopro BM (KR:247540)

Kinsale Capital (US:KNSL)

Super Micro Computer (US:SMCI)

The competition question is at the end for paying subscribers.

I’ll get to the point in just a minute, but first a word from our sponsor.

Expert calls just got easier.

Say goodbye to traditional expert networks with Stream by AlphaSense. Stream enables you to access high-quality expert insights, in less time and at lower cost. With proprietary search technology and a library of more than 26,000 expert call transcripts, Stream provides the tools to help you make smarter decisions faster. Sign up today.

Ben Inker on Value Investing

I recently attended a value investing conference in London. One of the highlights was a presentation from Ben Inker, GMO’s strategist, titled “Value Investing isn’t What you Think it is”.

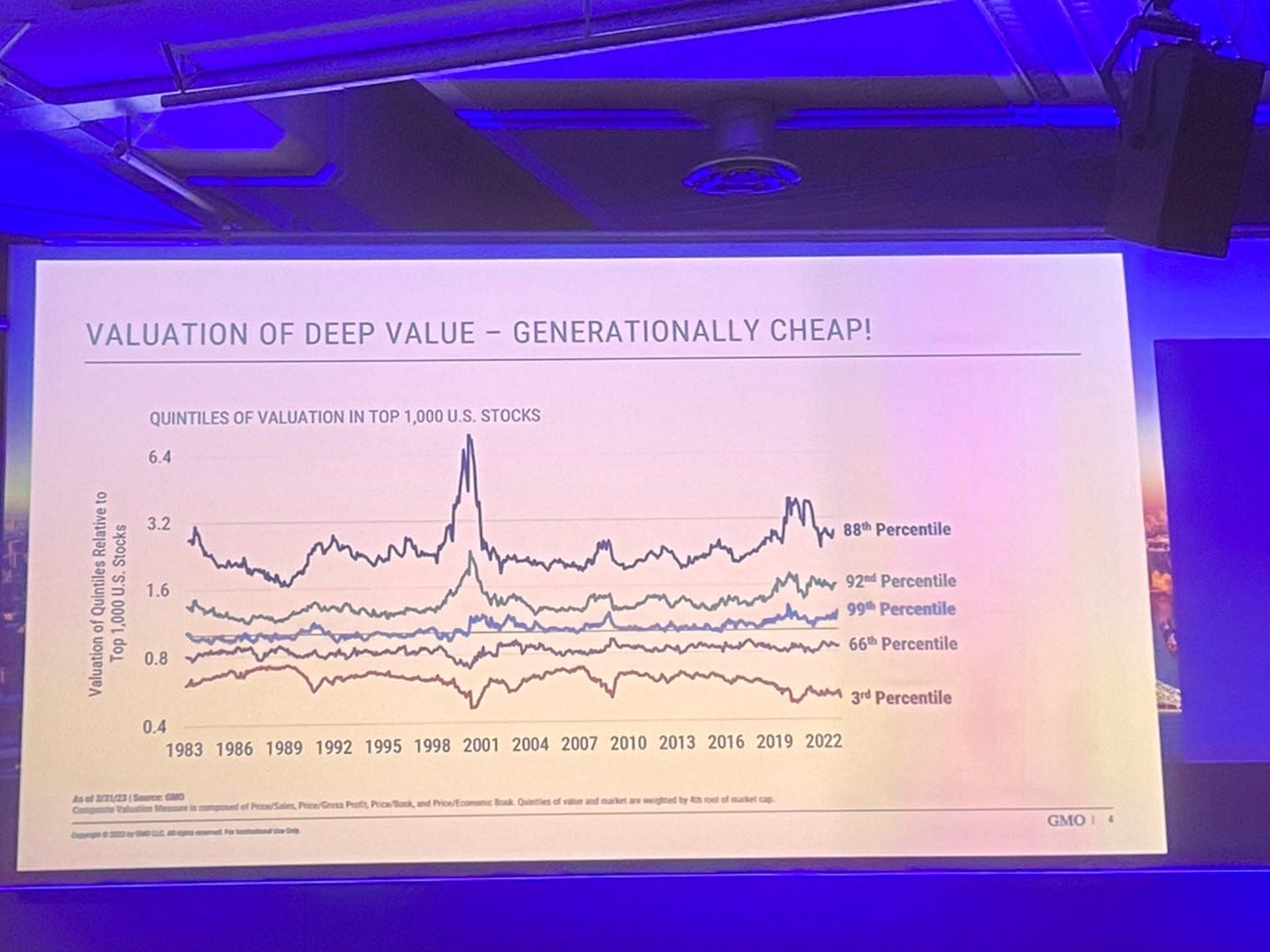

He mined GMO’s database looking at the difference between deep value (the cheapest quintile) and shallow (or ordinary) value (the second cheapest quintile). He explained that the spread of valuation across markets is critical to achieving outperformance. He also said that he believes today

“deep value is generationally cheap”

Inker showed that the most expensive stocks were in their 88th percentile of value and the cheapest were in their 3rd. This means they are almost as dear and cheap as they have ever been, with deep value stocks cheaper than they were in the dot com boom. Excluding financials only takes deep value up to its 5th percentile. So this is not simply about cheap banks!

Valuation of Value Stocks by Quintile: US

Source: GMO, author photo at conference

Interestingly, ordinary or shallow value (the second cheapest group) was in its 66th percentile, making it more expensive than normal. So if you’re looking for “generational” value, you need to go really cheap.

Inker emphasised that this was not a US phenomenon. Even if you exclude financials, and in every region globally, deep value is at a 1 in 20 year low.

Surprisingly, the most expensive stocks are even dearer outside the US. The cheapest stocks are almost as cheap and are still at extremely cheap levels. Regular or shallow value is cheaper globally than in the US. Note that the top 3 quintiles are all much more expensive than is normal, both internationally and in the US.

Valuation of Value Stocks by Quintile: Global

Source: GMO, author photo at conference

Rebalancing

One of the highlights of Inker’s presentation was his emphasis that rebalancing is key to the performance of value managers. He breaks down the 6.2% pa real return for the US market in the period 1970-2023 as follows:

70bps valuation change

280 bps income

250 bps real growth

Valuation change is what drives short term returns but is much less significant over the longer haul.

He then gave his breakdown of the relative performance of value vs growth over the same period, which gave a 3.2% relative return:

-130 bps valuation change

+230 bps relative income

-650 bps growth

+920 bps rebalancing

The rebalancing occurs when a stock leaves growth and enters value or leaves value and enters growth – it’s the rebalancing of the portfolio which delivers all the return. A stock will exit the value group when

It enters bankruptcy

It becomes too small for the universe

It is acquired (1% of the universe)

It has deteriorating fundamentals (value traps)

Its price rises and it becomes expensive

A stock will enter the value group when

There is an IPO of a cheap company (relatively unusual)

A small cap graduates to a larger stock universe

The price falls to make a growth stock cheap (12% of universe)

This rebalancing is therefore critical to performance, far more so than I had appreciated. Which means that value investing, at least as quantitatively practised, is NOT a buy and hold activity – you need to turn over the stocks.

Growth Traps vs Value Traps

Understanding value traps and their counterpart, growth traps (a term coined by Inker which I rather like), is helpful. Inker pointed out that growth traps are much worse than value traps because when a growth stock disappoints, you not only get the hit from the revision down of estimates, you also get a contraction in the rating which is often significant. Note that 70% of growth stocks did badly in 2022.

Inker defines a value trap or a growth trap as a stock which disappoints on revenue one year and its following year revenue forecast declines. He uses revenue because of the difficulty in defining which earnings to look at (GAAP or adjusted etc).

Value is the cheaper 50% of the top 100 US stocks, while growth forms the more expensive 50%, using their value metric which is a combination of valuation measures (so not just price: book or solely P/E).

Inker pointed out that although value traps get a lot of attention, his research suggests that growth traps are much more dangerous. When a growth stock disappoints, you not only get the hit from the revision down of estimates, you also get a contraction in the rating, which is often significant.

In a recent missive, Inker reviews the performance of value in recessions and asks why value doesn’t fare worse during a downturn. One reason is that growth traps fare even worse.

Value vs Growth Trap Returns

Source: GMO

Value traps attract a lot of attention and do a lot of damage to value portfolios, underperforming their peer group by more than 15% in an average year. They are well worth avoiding, but growth traps are significantly worse, underperforming the growth universe by 22.9% per year.

Value stocks which disappoint will of course underperform. But when a growth stock disappoints, not only are their fundamentals worse than expected, but they are less likely to continue being considered a growth stock. Growth stocks trade at a premium to the market and anything which calls that future growth into question will shrink that valuation premium.

Inker contends that value stocks and growth stocks are equally likely to disappoint in a recession. The difference is that when growth stocks disappoint, they are generally punished substantially more.

There is nothing new in this – it’s intuitive that a growth stock which disappoints will fare worse than a bombed out value stock. As I wrote here recently, David Einhorn said that he is buying stocks which are so unloved and so under covered that they can miss on earnings and the stock doesn’t move – the multiple may go from 5x to 6x, but nobody cares. The risk is much higher in a stock with a higher rating and greater interest. This is perhaps obvious, but I found Inker’s quantification helpful.

Conclusion

I learned three important lessons from Inker’s presentation:

Deep value is really cheap relative to history

Rebalancing a value portfolio is key to performance

Growth traps underperform 1.5x as much as value traps – best avoid both.