Balance Sheet First: The Rules Behind a $50bn Portfolio

David Samra’s investing playbook & the overlooked European stock we both like

I don’t often highlight the podcast in this newsletter — I assume most readers who like investing podcasts already tune in. But this month’s episode with David Samra is worth making an exception. His approach to value investing has crushed his benchmark for over two decades, and his insights are a masterclass in discipline, patience and competitive advantage.

In our conversation Samra said

…this notion of an efficient balance sheet, but that's garbage...why not have superior financial strength and give yourself a competitive advantage over other companies?

I have long been sceptical of the US CEO fashion to plump for buybacks, often without much careful appreciation of intrinsic value. One founder of a major US public company, a cyclical, admitted to me privately that he was a terrible judge of the share price and buybacks were usually an awful idea. Hence, I was pleased to hear David’s perspective.

Samra always asks CEOs what they see as the most simple competitive advantage that you could possibly have? For David, it's a strong balance sheet. More on his philosophy in a second.

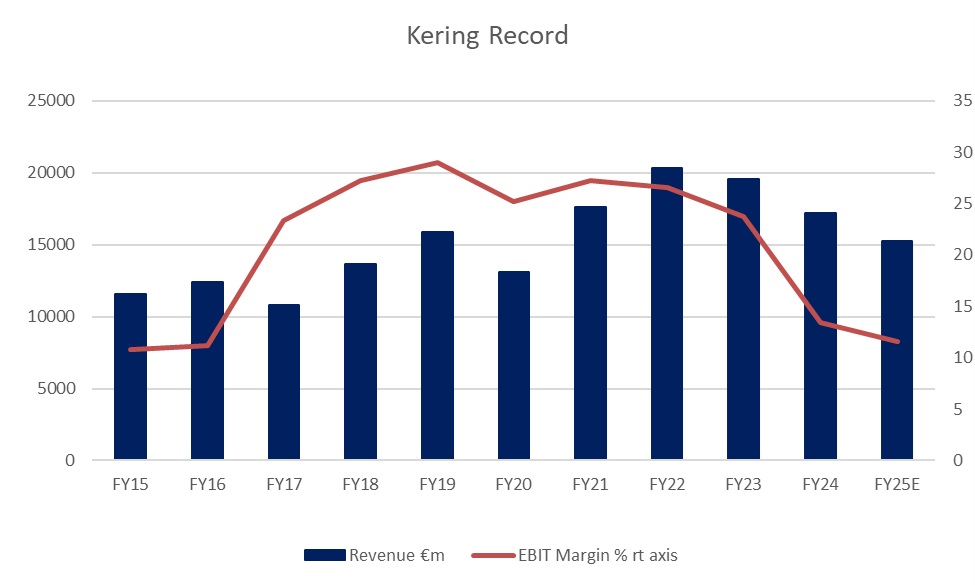

Kering

I have discussed Kering here before, and we chatted about it in this podcast. If you are interested in Kering, I suggest that you watch this AlphaSense recording, where I interviewed Sascha Rowald (former CEO of Birkenstock and now an advisor to Bernard Arnault), to get the luxury insider’s view of 1) what has gone wrong at Gucci and 2) how he would tackle the challenge faced by the new CEO of Kering (and the recently appointed CEO of Gucci).

The conclusion from the webinar was that this could be a long, hard and expensive struggle. Samra’s view on the podcast was that people will probably do well long term out of Kering, but it violated one of David’s fundamental principles – he will only invest in companies with strong balance sheets. Kering does not meet that criterion.

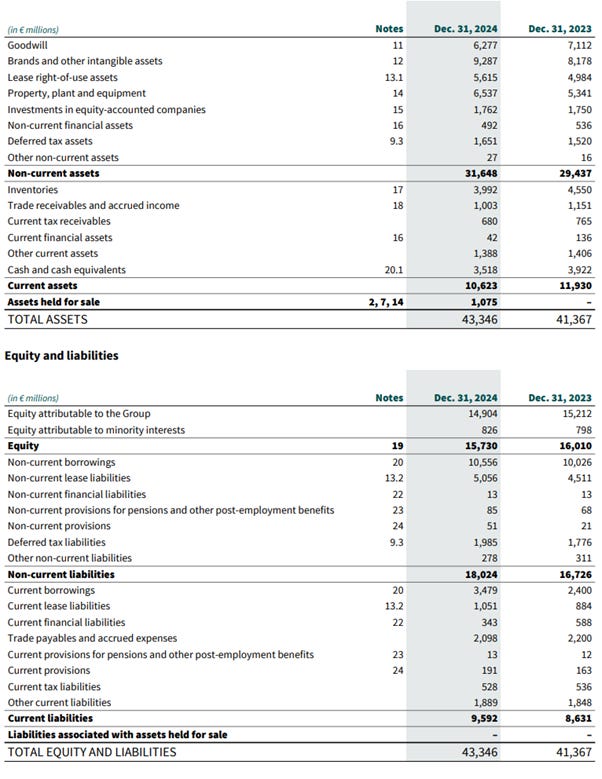

Kering Balance Sheet

Source: Kering Universal Registration Document 2024

Kering had long term debt of €10.6bn and short term debt of €3.6bn, and cash of €3.5bn, making net debt of €10.6bn excluding lease liabilities of €6.1bn, and a €0.1bn pension deficit. It had turnover of €17.2bn last year (€19.6bn) and an EBIT margin of 13.4% (23.7%). Its 10 year average EBIT margin is 21.7%.

Did you notice what I just did there? I didn’t mention the net debt to adjusted EBITDA number. Another fashionable parameter.

If you include the lease liabilities – Kering obviously has its own retail outlets – the debt is higher and looks more of a concern. I think it’s important to think about the coverage of interest and lease charges – assuming you can calculate the lease charges given the idiocy of the IFRS rules. I don’t really like the capitalisation of the lease liabilities, however, as companies have very different bases of calculation.

But using this imperfect measure, the total debt is close to the revenue number which is an issue – albeit, the margins are fat although both revenue and margins have been shrinking.

Kering Revenue and Margins

Source: Behind the Balance Sheet from AlphaSense data

I think it’s interesting to watch the webinar and listen to the podcast to get two different perspectives on this situation. In the Substack, I explained Causeway Capital’s view here, and I mentioned the debt then – it is increasing and will increase further.

Forensic Analysis Bootcamp

Good news: we are running our forensic analysis bootcamp again in the fall. It kicks off on October 6, and will run for 8 weeks every Monday night at 17.30 London, 12.30 EST, 9.30 PST. Classes run for 60-90 minutes and allow plenty of time for questions.

The curriculum is the full setup we offer to institutional investors but with some additional explanation and extra time allowed for a more considered deliberation. And every session is recorded so if you are travelling one week, no problem, simply watch the recording.

Samra’s Investing Philosophy

David Samra has been in the investment business for over 30 years. He specialises in international value and has beaten his index by over 4% pa for over 20 years, in a period when traditional value has been doing poorly. That may be why his fund, which has been closed to new investors for most of the last 14 years, has reached $50bn.

In the podcast, David explains his focus on four factors: owning good companies, buying them at a discount of at least 30% to intrinsic value, and ensuring they have excellent management and a strong balance sheet. And he discusses several of his stocks, sharing some impressively detailed knowledge.

Getting into Investing

David saw the value investing light when he took a class as an undergraduate which led him to study value investing at Columbia. On Fridays, he worked for famed value investor and former podcast guest Mario Gabelli, which was an excellent training ground. After 9 years as an analyst at two other shops, he got the chance to run his own fund at Artisan and he has been there ever since.

Managing a $50bn Fund

David talks of value investors generally, and himself specifically, as being the sort of people who like to run towards a problem. Typically when he invests in a new position, there is some issue depressing the share price. Given the size of the portfolio - $50bn across 40 positions - he is looking to put $1-2bn to work in any new idea, so he has to be early. That means he has to be patient and has to be prepared to buy more on the way down.

It also forces him to focus on the medium-term earnings power of a company. When the team underwrites the position, this is the key variable – it determines if the stock is cheap and it’s a measure which is less affected by the short term issues the company may face. Most stocks he buys have some (temporary, he hopes) issue which creates the share price opportunity.

He recognises that the stock may fall after he is built an initial position and is quite happy to average down. Indeed, he is relaxed about how long it takes the market to recognise the value; as long as his estimate of the earnings power is intact, he is content to wait; as long as the company is compounding its value over time, then he will be patient.

Active Investing

Samra is not scared to exercise his legitimate rights as a shareholder and to push companies towards the right strategy to benefit shareholders. He cites the example of Danone where he worked with the board to change first the CEO, then the Chairman. And he can point to a rerating of the stock as a consequence. David now sees this ability to engage with management and push for change as one of the tools in his toolkit. He describes this as active investing, but in contrast to activist investors, he generally operates behind closed doors. An exception is a letter to Samsung included with David’s 2024 shareholder letter.

Visiting Companies

In the podcast, David tells a brilliant story about how as a young intern for Mario Gabelli, he went to visit a company subsidiary in upstate New York and stole a march on the market. He still sees the need to visit companies as an integral part of his process, and spends a couple of weeks each quarter visiting companies. These include not just those he owns, their competitors and customers, but also dirt cheap stocks in the region and companies which don’t meet his value criteria today, but are good quality businesses that he might want to own one day – he then can wait for the opportunity when something goes wrong or the market gets bored.

We didn’t discuss this idea on the podcast, but David presented it at a recent value conference and it’s one of the most compelling pitches I’ve seen in some time. It's a turnaround story with credible execution, top-tier shareholder support, and a mispriced setup that reminds me of a past multi-bagger. Premium subscribers can read my full take and why I bought in.