I am a little dubious about the blind fashion for buybacks we have experienced over the last decade and more. Of course when money is free, it doesn’t matter how much you gear up - the more shares you buy back the better. But too few commentators ask if the stock is being bought back below intrinsic value which is of course the real test of added value.

With interest rates near zero, the arithmetic is compelling – a buyback will always enhance earnings per share. But it might not enhance shareholder value. Now money once more has a cost, and with credit becoming more difficult to acquire, it’s likely that more attention will be focused on those companies which have aggressively bought back stock but which have neglected the shareholder value test.

Before we get into all this, a word from our sponsor:

How can you get expert insights faster for 40% less?

Stream by AlphaSense offers access to our library of 26,000+ expert transcripts — plus the ability to engage with experts 1-on-1 and get your calls transcribed (free of charge) — all for 40% less than you would pay for 20 calls in a traditional expert network model.

S&P500 Buybacks – The 5 and 10 Year Record

I looked at the S&P500 and screened for share count declines and increases over the last 5 and 10 years.

S&P 500 Changes in Share Count over 5 and 10 Years

Source: Behind the Balance Sheet from Sentieo Data

The number of stocks is under 500 because there are companies with less than 5 years’ history and a number of companies with missing share count data. The ten year universe is slightly smaller than the 5 year.

In the most recent 5 years, just over 60% of the group saw an overall decline in share count, which is quite impressive given the natural trend to issue shares for stock options etc. Half the group saw a decline of under 20% and 10% had a decline of over 20%. The maximum was a decline of 50% which is over 10% pa and is really impressive. The distribution within rising share counts is more even and there are 4 companies whose share count has doubled or more.

Looking at the 10 year timeframe, the data is similar, with the population of larger increases and decreases rising at the expense of the smaller moves which is just as you would expect – the trends have persisted and companies have continued to buyback more shares. Again the split was 60:40 decreasing:increasing share count and 15% of stocks saw a ten year reduction in share count of 30% or more – that is meaningful.

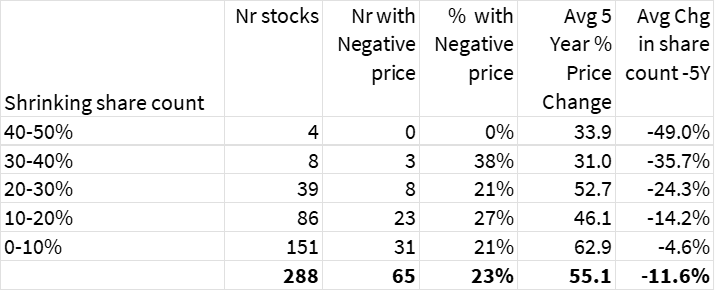

What is more interesting of course is whether the companies buying back shares performed better. I don’t want to pretend that this is an academically rigorous exercise – I shall save that for a later date when I look at the academic work. Bear in mind that I have not cleaned the data and the limited sample size. Here is the data for the stocks over a 5 year period:

5 Year Buybacks and Performance

Source: Behind the Balance Sheet from Sentieo Data

The average price change does not increase with the percentage of stock repurchased – the bigger universe of stocks with smaller buybacks performed much better than the stocks with the larger percentage buybacks. But this larger group also saw quite a few stocks which lost money, although interestingly this didn’t drag down the overall performance.

Stocks which had significant increases in their share count – above 35% - saw a slightly worse performance overall (+37%), but there were only 35 in total, so I am not sure that one can draw any conclusions. They certainly didn’t have a really bad result.

I did the same analysis over the 10 year timeframe – a negative result is much less likely given the strength of the stockmarket and indeed the incidence in the table (and in the stocks whose sharecount grew (not shown)) is much lower.

10 Year Buybacks and Performance

Source: Behind the Balance Sheet from Sentieo Data

The price performance is also much stronger over this timeframe but again there is not much to choose in performance terms between those doing smaller vs larger buybacks. The frequency of these larger buybacks is surprising – 4% of stocks shrunk their share count by over 40%, 13% of stocks shrunk share count by over 30% and 28% of stocks shrunk their share count by 20% or more over the last 10 years.

This has been a popular trend, which makes sense, given the plentiful availability and cheapness of money in the last decade. I wonder how enduring it will be over the next decade.

Xerox vs eBay

The 10 year trend provides two interesting and contrasting examples which illustrates clearly why buybacks are not necessarily a good thing, even in a zero rate environment. eBay saw a near 60% decline in its share count over the last 10 years vs over 50% for Xerox. eBay saw an 85% price appreciation in the period, while Xerox saw a 37% decline.

And the poor stock price performance of Xerox is simply down to poor operational performance. Here is the chart of the revenues of the two businesses:

eBay vs Xerox Revenue Index

Source: Behind the Balance Sheet from Sentieo Data

Xerox’s revenues shrank significantly and of course profits followed:

eBay vs Xerox Adjusted EBIT Index

Source: Behind the Balance Sheet from Sentieo Data

This translated into a downward net income trend which was partially mitigated by the buyback programme – the blue lines in eth chart below. IN contrast, eBay didn’t fare brilliantly in net income terms (I assume the Paypal spinoff) but the buyback programme really benefited the eanrings per share trend.

eBay vs Xerox Adjusted Net Income and EPS Trends as Indices

Source: Behind the Balance Sheet from Sentieo Data

Xerox shareholders would almost certainly have fared better if management had simply given them the cash by way of dividend. In the last 10 years, Xerox paid out $2.4bn in dividends and spent $5.6bn on buybacks. Since 2010 dividends have totalled $3.1bn and buybacks $7.2bn. The market cap today is $2.2bn and the balance sheet carries $3.7bn of debt and $1.0bn of cash; there is also a $1.4bn pension and medical benefit liability and $3bn of finance receivables.

Perhaps if management had been slower to buyback stock, the cash used would have gone further. And this is my main point – many corporates are quick to buyback stock but slower to understand that it’s only worthwhile if the stock is cheap – Buffett of course makes his buybacks highly selectively.

Paying subscribers will receive a link to the spreadsheet if they wish to download it.

In a future article, I shall look at the academic literature on buybacks. I am interested to see if there is any evidence that companies which buy back stock do better than those which do not. Intuitively I would guess not; my brief screen suggests not; but I am looking forward to reviewing the evidence.