Introduction

In a recent post, I highlighted that several presenters at a Quality Growth Conference in London, all professional managers of such funds, said that assessing management is a key factor in how they find high quality companies.

I have always found such commentary interesting, as management is one of the hardest factors for the analyst to assess. To do it, there are a number of techniques of varying effectiveness:

Check their CV

Look at their track record in prior roles

Peruse their social media accounts

Ask peers or the sell-side how they rate them

Meet management and make your own assessment

Assess their strategy

Assess their capital allocation performance

Check their CV

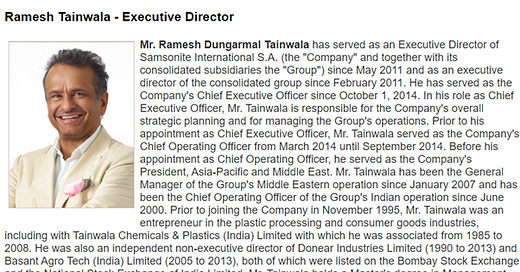

Few investors bother to look closely at managements’ CVs. They have in effect outsourced the due diligence to the company’s HR function. While investors and the sell-side might have a quick glance at the manager’s bio, short sellers are the only people I have seen do proper due diligence in this respect. A great example is the former CEO of Samsonite, Ramesh Tainwala.

I once went to a lunch with Tainwala, as I had an interest in Samsonite (not my best ever recommendation, but it performed OK for us). The lunch was best described as weird. I left with a friend who works as a global manager for a $1tn+ manager and we agreed that we felt uncomfortable with the CEO.

Tainwala spent a large part of lunch talking about the company’s Tumi acquisition and how Japanese clients insisted that each pocket of the Tumi backpack (lots of compartments) should have a designated function. It really was strange, given that I remember it so clearly, among hundreds of such lunches. Here is his bio, taken from the company’s website:

Source: Samsonite.com

In this biography, Tainwala is referred to as Mr, and only his Indian Masters is listed as a qualification. Elsewhere, he claimed that he was Dr Tainwala and had a PhD from Cincinnati University. Short seller Blue Orca Capital attacked Samsonite for spurious comments in its financial filings and some related parties transactions that looked odd but not material. But Blue Orca really struck home on the doctorate. Tainwala was forced to admit that his CV was fake and then resigned as CEO.

If the company’s HR department cannot be bothered to check that the CEO’s qualifications are real, I’m not sure there is much that can be done. I don’t think investors have either the time or the inclination to check that management are honest and haven’t lied on their CVs. But it’s probably worth looking at the CV and ensuring there is nothing obvious – too many roles, gaps between roles etc. If there is no detailed bio on the company website or via Google, you can best do this by perusing the executive’s LinkedIn page, although it’s easy to omit roles or fudge dates on there. I don’t think any such CV review would be conclusive.

Extract from Blue Orca Report

Source: Blue Orca Capital Report on Samsonite

Track Record In Prior Roles

I recall meeting one of Bill Ackman’s team who explained that he had spent a month assessing a new CEO, appointed to lead a company in which their fund had invested. He explained that he as an expert in this, as he had a background in private equity. I asked him what criteria he considered especially relevant and he explained proudly:

“ROIC.”

When I questioned him more closely on how he assessed this, there was a lot of confusion and extended explanations. I don’t think ROIC is a good way to assess a CEO’s ability to achieve an operational turnaround (which this business required). A positive result on ROIC might reflect managerial skill, or that the business was levered up, or that the earnings were made up or that the tax rate was manipulated or a combination of all three (only one of these was tested by that analyst).

It's important to check the record against a relevant peer group, assessing margin performance and relative returns. But you need to look at the record under this executive’s leadership vs prior leaderships. If you walk into the job at a market leader – think Coca Cola or similar - and don’t do much, the chances are that the returns will still look pretty good. But that doesn’t make you a great leader or able to transition.

And this issue of transition is important – a CEO might look brilliant in one industry and not cope well in another; or outperform in one geography and fail in a second (think UK retail transferring to the US for example). A manager could also deliver in one style of business but do less well in another which has a different capital intensity, for example.

Social Media Following

If you think you are safe with someone because they have a lot of followers on LinkedIN or Twitter, think again. Charlatans who will defraud you or simply cause massive wealth destruction often have large followings.

Wirecard had 117k followers on Twitter and 90k on LinkedIN. A high follower count tells you that a company or individual is effective at attracting a following, but this can be achieved through promotion or through bots. Many younger people are mesmerised by follower count and honestly, it’s not that important (says @steveclapham with 11k Twitter followers, not sore). And it’s certainly not relevant to making money in equities.

Chamath Palihapitiya is certainly super smart and has 1.6m followers on Twitter; yet investors in Virgin Galactic are down >90% from the peak or >50% from the SPAC price. Admittedly, he isn’t the CEO of that company, but he was the promoter. He has cleverly capitalised on his following and personally made serious money on that transaction.

I am not suggesting you ignore social media. Looking at an executive’s posts might give you some insight into the way they think, although often the posts are managed by the PR team (or even a secretary, as one leading entrepreneur admitted to me recently). I like to look but remain sceptical. This applies beyond social media of course.

Ask peers or the sell-side

Many portfolio managers talk to other fund managers or even sell-side analysts to form or confirm an opinion on management. The problem is knowing how much weight to put on someone’s opinion. An old friend of mine is a top head-hunter. He is really smart; he knows his clients intimately and he spends several hours one to one with each candidate, as well as doing intensive background checks and deep research. He reckons he is outstanding at assessing talent. I used to be inclined to believe my friend’s rhetoric, as he has always made a lot of money and he is quite persuasive. But I have always wondered how much of his success came from sales acumen and how much was genuine talent scouting ability.

Fund managers are rarely great judges of management talent. One successful manager I know admitted to me that he was useless at it. Another claims (in his marketing literature) that it’s one of his great skills, yet he has invested in more companies that have gone bust than some VC investors.

The skills that make a great fund manager – confidence in their own ability; ability to ignore the noise of the market; vision of the future; analytical talent; and ability to understand numbers – are not necessarily conducive to fantastic inter-personal skills nor to ability in assessing management. One area where many managers are skilled is in watching body language and judging if someone is lying. But it’s far from a given that portfolio managers will be as competent at assessing management teams as they are at assessing share price potential.

Meet them yourself

James Montier at GMO thinks that it’s dangerous to meet management. CEOs of Fortune 500 companies are often charismatic, persuasive and great salespeople. They are experienced in persuasion, having succeeded in rising to the top of these organisations. Their IR teams produce convincing arguments, persuasive bullet points and attractive PowerPoint presentations on strategy. How much chance does an investor have? Terry Smith follows a similar argument – you don’t need to meet the management as the answers are all in the numbers.

As ever with investing, you must do what suits your personal style and recognise your own abilities and limitations. Paying subscribers can read about my approach to meeting management at the end. Private investors may not be able to meet managers one to one, but they can watch capital market day presentations or similar, while maintaining a sceptical stance.

Assess their strategy

When a CEO of a large public company discusses strategy, it has usually been pored over by internal management – and quite possibly external consultants like McKinsey – and been honed into a powerful presentation. It really should be bulletproof and no investor should be able to pick holes in it. But it’s surprising how often a simple question on returns can wrong-foot an able executive.

I recall one hapless airline CEO who was unable to predict the business/leisure mix after the introduction of more upscale business class and premium economy products. They hadn’t really thought through the increased dependence on corporate travel, at a time when budgets were likely to come under pressure.

Most of the time, the manager should be able to convince you of the strategy – if they cannot, you really ought to consider whether you can continue the position. If nothing else, you will kick yourself if the strategy which you didn’t believe in turns out badly and the share price suffers.

Assess their capital allocation performance

Discussing the strategy isn’t a brilliant method and it can only take you so far. It’s better to try and understand if this management team has been effective at making capital allocation decisions in the past. I look at three elements of capital allocation:

Organic

Buybacks

Acquisitions

The impact of a new CEO’s organic capital allocation decisions depends on returns and dividend payout. For some CEOs, these decisions will take several years to impact the overall return of the group; while for others, returns can change more quickly. I shall return to this important subject in a future article.

Simplest and often critically important is issuing and buying back stock at the right times. Some managers are good at this and should be backed; some are awful and should only be backed if the valuation or growth opportunity provides extra protection.

I am more ambivalent about acquisitions. It’s tempting to bin the stock run by an idiot who has done a daft deal, but it may not be a great strategy. Paying subscribers can read on to find out why.